Many civil society and academic projects are engaged in documenting and analyzing conspiracy theory, anti-democratic or racist discourse on social media. Kilian Buehling has investigated to what extent the results of these efforts are influenced by the time of data collection. In this article, he summarizes the results of a recently published study.

A bizarre picture must have presented itself to new Twitter users joining the social media platform in 2021: They had read a lot about ousted President-elect Donald Trump’s offensive posts, disinformation campaigns amid the COVID-19 pandemic, and the constant danger of disappearing into a conspiracy theory echo chamber. But by mid-2021, there was no trace of many dubious online personalities and their posts. On the contrary, social media platforms went out of their way to provide COVID-19 misinformation with comments that shed light on its factual accuracy. For a brief moment, the digital world seemed fine. This was due to the (now lifted) suspension of Donald Trump’s Facebook and Twitter accounts, as well as extensive moderation decisions by various platform operators that resulted in post deletions and account suspensions. However, the now-invisible posts had already reached their intended audience. The U.S. Capitol was stormed. The intended damage to democratic institutions was accomplished. Today, after the Twitter suspensions of Donald Trump and other actors banned for their anti-human and anti-democratic behavior were lifted, all users can read their derogatory posts again. Even on this small scale, it is clear that the conclusions that users draw about the state of the digital world depend on the moment of observation.

Alternative social media platforms and the continued visibility of conspiracy theory posts

With their moderation policies, the major social media companies have succeeded in getting many of the former right-wing hate speakers to leave the mainstream platforms for good. But wherever demand exists, supply soon follows. A fast-growing right-wing alternative social media ecosystem has been courting the new users, allowing them to engage in anti-democratic and anti-human discourse as uninhibitedly as possible on their platforms. For example, the Twitter clone Gab or the YouTube clone BitChute1 experienced a boom in user activity. However, the most important platform for conspiracy theories and anti-constitutional mobilization in the German context is undoubtedly Telegram, which has become known as the main communication tool of the “Querdenken” movement in Germany. The messenger service differs from its competitors such as WhatsApp or Signal in that it allows public communication: In broadcast channels, administrators can write messages to all subscribers, like in a blog. This allows them to reach thousands of interested people at the push of a button.2 In public chat groups, all users can also participate in the discussion. The threatening potential for radicalization in the right-wing conspiracy theory milieu on Telegram3 is therefore increasingly the focus of civil society initiatives and academics who point to the dangers of the spread of conspiracy theories.

» But while moderation and account suspensions are the exception on Telegram, not all content shared on public channels and groups will remain visible forever. «

But while moderation and account suspensions are the exception on Telegram, not all content shared on public channels and groups will remain visible forever. Existing posts can be sanctioned and deleted by group members and administrators. The reason for this may be personal community norms4, shame5, or fear of the consequences6. As described at the beginning, messages can reach many people in this way and still remain invisible in hindsight.

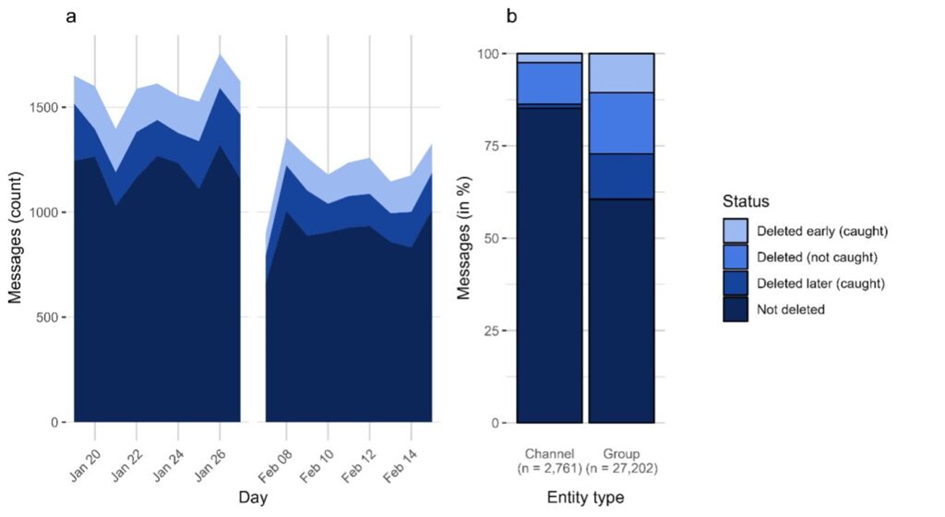

When dealing with any social media data, researchers are therefore advised to always consider the extent to which message deletions may systematically bias their own results. In the recently published study “Message Deletion on Telegram: Affected Data Types and Implications for Computational Analysis,” a sample of right-wing conspiracy theory Telegram chats was examined for subsequent deletions. For this purpose, 25 channels and 25 groups were queried every half hour to register all new posts and to anticipate possible deletions. We aim to assess the extent to which deletions can lead to systematic biases in research results by making this survey as complete as possible.

A first overview showed that on average only 88% of the sent messages are available after five days. After seven months, only 83% are still available. In chat groups, even more messages are deleted: After five days, only 64% of the messages are still readable, and after seven months, it is only 52%. This discrepancy may caused by using moderators and chat bots in the groups.

» After seven months, only 83% are still available. In chat groups, even more messages are deleted: After five days, only 64% of the messages are still readable, and after seven months, it is only 52%. «

The types of messages that are deleted also differ between these two types of public communication: In chat groups, it is primarily text messages that are deleted. In channels, a disproportionate number of shared messages from other channels and videos are removed.

Message deletions and their impact on computational analysis methods

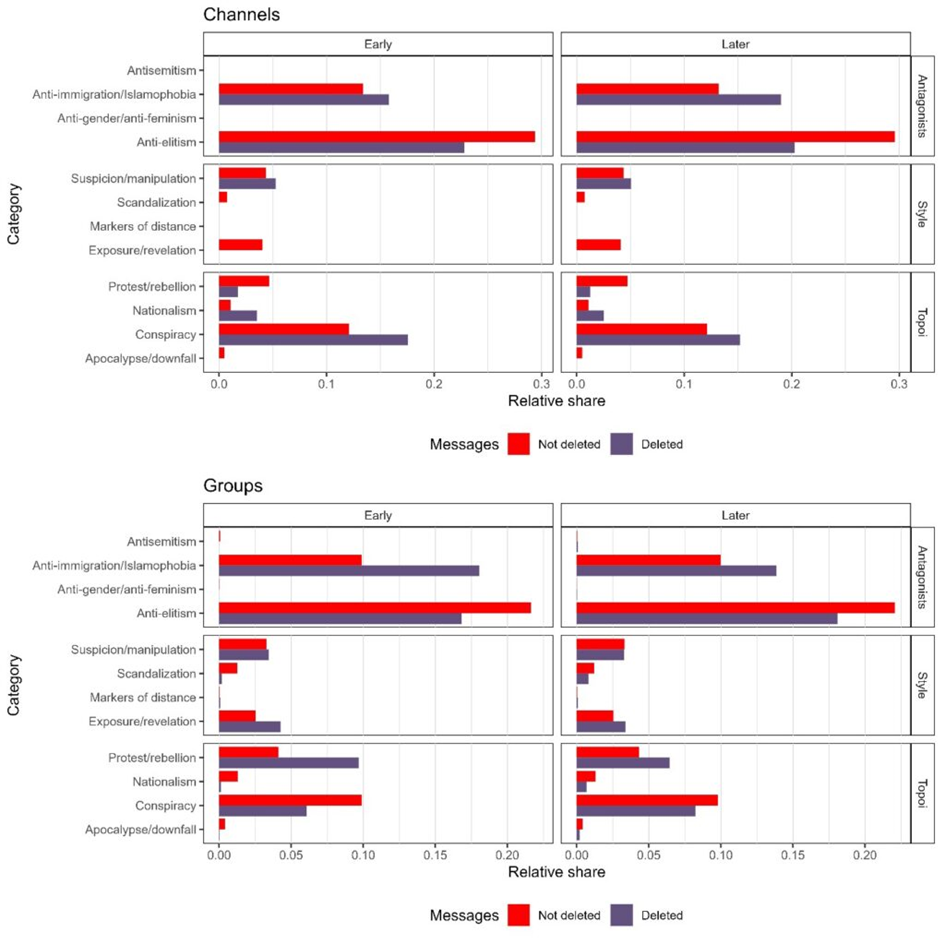

For quantitative analyses of this communication data, such deletions would be largely unproblematic as long as they were randomly distributed. However, when posts are deleted not at random, but to make certain types of content unseen (and thus supposedly undone), they can alter the research results. Therefore, we examined the results of several analytical methods commonly used in the study of right-wing conspiracy theory social media communication.

In order to better identify different thematic facets of right-wing populist conspiracy theory discourse, the classification dictionary “RPC-Lex” was recently published7. It contains an extensive list of keywords. Their occurrence in a social media post can give an indication of the discursive patterns contained in the message. Comparing deleted and undeleted messages, it is clear that Islamophobic posts are often deleted. Conversely, anti-elite messages are more common among permanently readable posts than among posts that have disappeared. Thus, by ignoring deleted messages, this dictionary analysis would underestimate the proportion of Islamophobic posts while overestimating the emergence of anti-elite messages.

» A comparison of deleted and undeleted messages shows that Islamophobic posts are often deleted. «

Other computational content analysis methods, such as topic modeling or word embeddings, use automated procedures to extract linguistic patterns and themes from large text corpora. The non-random deletion of posts can also lead to varying degrees of bias in the results of these machine learning methods. Network analyses that examine the relationship between Telegram channels and their embeddedness in cross-platform information ecosystems8 may also be biased by message deletion. However, it seems unlikely that the general trend of the results will change fundamentally.

What is to be done?

Given the potential for bias highlighted in this study, how should Telegram data analysts deal with their potentially incomplete data? The first suggestion that emerges is that data collection should start as early as possible! The larger the time gap between the original message and its collection, the higher the probability of its deletion. Thus, it is also worth planning a data collection phase spanning over a longer period of time in order to collect the messages of a Telegram channel at as many points in time as possible (e.g. daily or weekly).

» The larger the time gap between the original message and its collection, the higher the probability of its deletion. «

Of course, such planning is not always possible because the analyzed period often lies in the past. Nevertheless, it is possible to determine the number of missing messages to get at least an estimate of the data loss. In addition, as always, cooperation between scientists is worthwhile: Perhaps a colleague accessed the same channel earlier when more messages were visible?

Finally, this study is a contribution to a reliable and reproducible methodology for analyzing a platform that, at least in the German-speaking world, has gained notoriety as an incubator of anti-democratic movements.

The full paper is available as an open access publication. The paper, “Message Deletion on Telegram: Affected Data Types and Implications for Computational Analysis” was published in the journal Communication Methods and Measures and can be found here: https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2023.2183188. The study was developed within the NEOVEX project, which was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) as part of its “Research for Civil Security” program.

This blog post was originally published in German on the NEOVEX website by Kilian Buehling in April 2023.

- Frischlich, L., Schatto-Eckrodt, T., & Völker, J. (2022). Withdrawal to the Shadows: Dark Social Media as Opportunity Structures for Extremism. CoRE – Connecting Research on Extremism in North Rhine-Westphalia, 3, 39. https://www.bicc.de/publications/publicationpage/publication/rueckzug-in-die-schatten-die-verlagerung-digitaler-foren-zwischen-fringe-communities-und-dark-so/

- Schulze, H., Hohner, J., Greipl, S., Girgnhuber, M., Desta, I., & Rieger, D. (2022). Far-right conspiracy groups on fringe platforms: A longitudinal analysis of radicalization dynamics on Telegram. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 28(4), 1103–1126. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565221104977

- Ebenda.

- Gagrčin, E. (2022). Your social ties, your personal public sphere, your responsibility: How users construe a sense of personal responsibility for intervention against uncivil comments on Facebook. New Media & Society, 146144482211174. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221117499

- Almuhimedi, H., Wilson, S., Liu, B., Sadeh, N., & Acquisti, A. (2013). Tweets are forever: A large-scale quantitative analysis of deleted tweets. Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 897–908. https://doi.org/10.1145/2441776.2441878

- Neubaum, G., & Weeks, B. (2022). Computer-mediated political expression: A conceptual framework of technological affordances and individual tradeoffs. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, 0(0), Article 0. https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2022.2028694

- Puschmann, C., Karakurt, H., Amlinger, C., Gess, N., & Nachtwey, O. (2022). RPC-Lex: A dictionary to measure German right-wing populist conspiracy discourse online. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 28(4), 1144–1171. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565221109440

- Heft, A., & Buehling, K. (2022). Measuring the diffusion of conspiracy theories in digital information ecologies. Convergence, 28(4), 940-961. https://www.doi.org/10.1177/13548565221091809